My father occupies any space he is in with a stoic, silent, and monumental presence. His impassive demeanor has prompted us to call him (behind his back, but with the greatest of affection!): The Easter Island Head.

When he was an active minister, my father would break his silence once a week on Sundays to preside over a Korean congregation in Northern Virginia. For one hour a week, between the hours of eleven and twelve, he would undergo a remarkable transformation. I couldn’t understand the sermons he would preach, but I could practically surf along the dramatic swells and crests that would come billowing into the pews from the pulpit. His animated face would glow and he would gesticulate to emphasize a point. Every once in a while, the congregants would burst into appreciative laughter and I would wonder what he could have possibly said that was so funny. During the hymns, he would forget to step away from the microphone, so his strong, fine voice could always be heard over everyone else’s. At the stroke of noon, the spell would be broken. He would fall silent and the impassive façade would settle back over his features like a mask, and would remain there until the next sermon he gave, or the next class he taught.

Only one other circumstance would cause the stony exterior to fall away to reveal the gentle river of memories and deep emotions that, in truth, have always floated fairly close to the surface. Within the close circle of his own immediate family, my father would often talk about his difficult childhood. Unlike my mother, who buries the unhappy memories of her past in some secret, inaccessible vault to which only she has the key, my father seems compelled to share his personal history through the stories he repeats over and over in an almost ritualistic way. Though I’ve heard them countless times, I never get tired of listening. When my father tells us about his childhood, and about the deaths of his father and siblings in his quiet, measured tones, it feels as if we are partaking in a sacred rite of remembrance to honor family members we would never know.

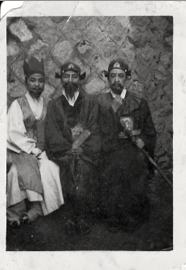

Dad’s mother and four brothers who survived to adulthood

My father’s family lived in the country. They lived through the Japanese occupation, World War II, and the Korean War. Life was a struggle. Disease was rampant. When he was eleven years old, his entire family was struck down by typhoid fever for two weeks. Only his mother did not get sick, because she had already survived her own bout of typhoid fever as a child. By the end of those terrible two weeks, my father’s father was dead. He left behind a widow with ten young children and a farm to run. This disastrous change in the family’s fortunes unleashed a whole chain of calamities.

To save grain, the family would skip lunch and only eat twice a day. My father watched three sisters and two brothers, between infancy and second grade, succumb to malnutrition and disease. Of all the siblings he lost, the one he talks about most is a beloved younger brother, who died at the age of four.

Whenever he speaks of this brother, he prefaces everything by saying that he was a genius. He always mentions his enormous head.

“Other than his big head, how could you tell he was a genius, Dad?” I asked, when he spoke of him most recently.

“I would carry him on my back and teach him Bible verses. I would recite a long passage such as Psalm 23rd just once, and he’d be able to repeat it back verbatim.”

He continued, “We had gotten used to the sound of WWII B-29 bombers. But when the communists overtook our village, American sabre jets flew over for the first time. We had never heard them before, and the noise…it was like a terrifying thundering metallic sound raining down from heaven.”

My father’s little brother was already weak and ill, but he thinks it was the noise of the sabre jets that literally scared him to death. When they would pass over, he would tremble with fear. Every time he would start to recover from the shock, another jet would fly over and he would get sick again.

There wasn’t enough to eat, and no one could risk going outside to forage for food for fear of falling bombs. “He would have survived if we had paid more attention,” my dad concludes. After a long pause, he says, “I really wished I could have caught bullfrogs to feed him.”

In the past my mother would try to comfort him when he finally arrived at this sad conclusion. She would say, “You were just a child. There was nothing you could do. It was too dangerous to go outside.” Nowadays, we all remain silent.

This last time, there was a coda to the story. My father told me that he was flying into LA for a conference when they announced over the intercom that the U.S. had just invaded Iraq.

“I was shocked when people started cheering. These people had never lived through a war. I immediately thought of the women and children, who would be terrified. When we landed and were arriving at the airport, everyone looked excited and happy…”

He shook his head in dismay and grew silent.

“I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I thought to myself that if they had ever lived through bombings, they would never be cheering for such a thing.”

Though he only lived four short years on this earth, my father’s little brother lives on through the words of his loving brother, and the burnished memories he has passed on to his own children.

Psalm 23

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

Related post: Little brown haired girl

I always had a dog when I was growing up in Korea, but I don’t like having a dog here. I feel sorry for dogs in America. In Korea, no one kept dogs in the house or on a leash. The dogs would be fed in the morning and then they’d join the rest of the village dogs. They would roam free in the fields all day long…huge packs of them. There would be fifteen to twenty dogs running around together all day long, having so much fun. In the evening, they would go back to their own houses and eat whatever scraps they were given.

I always had a dog when I was growing up in Korea, but I don’t like having a dog here. I feel sorry for dogs in America. In Korea, no one kept dogs in the house or on a leash. The dogs would be fed in the morning and then they’d join the rest of the village dogs. They would roam free in the fields all day long…huge packs of them. There would be fifteen to twenty dogs running around together all day long, having so much fun. In the evening, they would go back to their own houses and eat whatever scraps they were given.