My mother is a force of nature…

I’ve re-posted this one once already, but I can’t resist posting it one more time.

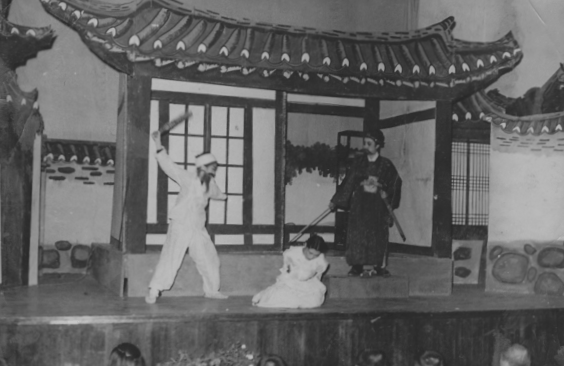

My dad told us that he heard about my mother before ever setting eyes on her. According to him, Seoul was abuzz with excitement about her acting. This horrified and mortified my grandmother, who considered acting a déclassé pursuit not too far removed from prostitution.

Although my mother gave up stage acting after college, she has worn the tiara of an inveterate drama queen all her life. She is brash and sparkling: like a firecracker rather than a candle. It was a cosmic accident that my mother was born in Korea, and not in America. Korean women titter hesitantly with their heads bowed and a hand covering their mouth; my mother throws her head back and guffaws raucously. When she’s happy, she trills like a bird. When she’s angry, her eyes blaze, the moon eclipses the sun, and darkness falls heavily upon the cold earth.

Her exceptional acting skills have been called into service many times over the years. A Korean couple once called my parents in the middle of the night to ask them to accompany them to the emergency room so that they could help interpret for them. They waited in the emergency room for hours while the woman’s condition worsened. She was doubled over in agonizing pain, but was still made to wait. Suddenly, my mother stood up and started screeching at the top of her lungs like a madwoman, “This woman is DYING! She’s DYING and NO ONE IS TAKING CARE OF HER! SHE’S GOING TO DIE, RIGHT HERE IN THE WAITING ROOM!” Later my mother reported burning with shame and embarrassment as she created the scene, but she didn’t stop screaming until the orderlies rushed over and wheeled the woman away. When the doctors came back, they reported that the woman had had an ectopic pregnancy, and had indeed been minutes away from dying when my mother gave the spectacular performance that saved her life.

My mother continued to hone her craft over many years and in many venues. Bank performances became her specialty. In fact, torturing bank employees across America and getting them to do her bidding became something of a hobby for my mother. As she can’t drive, she would have me take her to the bank. My mother would sit silently, clutching her big shabby purse on her lap until called, whereupon she would blink her eyes like a dazed little bird and wander into the cubicle of her next victim. The affable bank employee would size up this little old lady, crack a few genial jokes, make a few pleasantries…And then my mother would begin.

“Now. I received this letter from you telling me that my CD matured. I would like to withdraw my money, please.”

“Ah, yes, Mrs. Kim, but it’s now July 15th, and the deadline for withdrawing was more than two months ago.”

“Yes. I understand. But I was in Korea, and I couldn’t come until today.”

No matter what the banker said, no matter how patiently he would point to the date long passed, my mother would just keep repeating her request over and over in the same mild-mannered way.

“I couldn’t come by May 1st, because I was in Korea. My flight arrived only a few days ago. I was sooo jetlagged, but finally I was able to come today. And I would like my money now.”

It would go on like this for a good ten minutes. “Pooooooor sap,” I’d think to myself as I would watch the banker squirm like a pinned insect. Finally, he would succumb to the inevitable and hand my mother whatever she wanted on a silver platter. I imagine those bankers consoled themselves with the thought that they were doing a good deed for this dear, confused little kitten. If they had paid attention, though, they would have witnessed a remarkable metamorphosis as she strode out the door counting her bills like a Korean Keyser Söze.

Her own family was treated to the theatrics as well. When she thought we were watching too much T.V., for example, she heaved the set into the driveway, pulled the plug out from both ends, and chopped the cord into a million pieces. When I was struggling to finish my Ph.D. with a toddler and an infant to care for and was ready to give up on the whole project, my mother called me one day and pleaded in a voice overwrought with emotion, “Just finish it for your father’s sake. It would mean so much to him. Please. Do this one last thing for him, before he dies.” Never mind that he was in perfect health, the dissertation got written that year.

About four years ago, we almost lost my mother. She was diagnosed with primary amyloidosis and given eighteen months to live. She came back to America to be treated at Sloan-Kettering through a clinical trial of a chemotherapy drug. When it was clear that the treatment would kill her faster than the disease, she was kicked out of the trial, but she had had just enough chemo to knock her disease into remission. Fiercely independent, though still weak as a newborn lamb, she insisted on dragging herself back to Korea on a 20 hour flight, against doctors’ orders and despite the entreaties of her family. My dad shudders when he recalls her lying on the airport floor from sheer exhaustion during a layover. She broke three ribs the day after arriving when she tripped over the suitcases she was too tired for the first time in her life to unpack the minute she arrived, but she had triumphed. Giving Death the finger, she had staggered back to her own apartment, and her own life. We went to visit my parents that summer and met my father’s assistant minister. This grown man in his thirties, married with two children, confessed to my brother in his heavily accented English, “I am scared of your mommy. But I love her.”

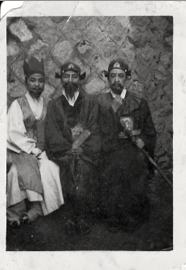

Honestly, I could write a whole novel about this woman, but I’m too scared she might read it and I’d be in big fat trouble. Instead, I’ll leave you with some photos of my mama, the Drama Queen from her early acting days.

There she is……….on the left!

In these next two photos, she’s the badass on the right.