I’ve been reading Wallace Stegner’s Crossing to Safety, which traces the course of a friendship between two couples across decades. The husbands are both English professors and aspiring writers. One of them is a poet. In one scene the poet visits his then-girlfriend’s house and is drawn into a debate in which he is obliged to defend his wish to retreat like Yeats into a “bee-loud glade” to write poetry. “Poetry isn’t direct enough most of the time,” his soon-to-be wife protests, “It doesn’t concern itself with the vital issues. It may be nice to know how a poet feels when he looks out his window into a fresh snowfall, but it doesn’t help anyone feed his family.”

The same day I read this passage, I happened to read an interview with one of my favorite poets Li-Young Lee. He reveals that there was a period in his life when he wanted to quit writing poetry because he felt that writing poetry was inconsistent with the life of activism that he was trying to lead. He tried to set poetry aside, because it “didn’t do anything.” (“The Totality of Causes: Li-Young Lee and Tina Chang in Conversation“).

Of course, this is a debate that has been going on for centuries. Does art have intrinsic value, or does it need to “do something”? Can we subject art to a value scale based on its utility? Where would utilitarian art or purely aesthetic art fall on such a scale?

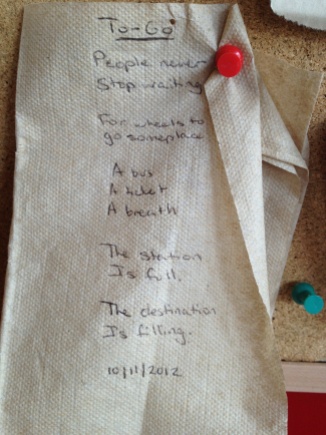

I was delighted to discover the “Revolutionary Poetry” wall in Revolutionary Soup, a restaurant on the Corner in Charlottesville. Every time the door opens, the scraps of paper and napkins on which poems have been written flutter in the breeze. Some of the poems are quoted, some have obviously been written on the spot. “Leave one, or take one as you see fit,” says a card tacked up in the upper left hand corner. The poetry board encapsulates many of the reasons why poetry really does matter, and how it “does something.” Poetry inspires people to contemplate and interpret life through an aesthetic prism that demands a certain amount of concision. A poem’s brevity allows it to become a commodity or a gift that can be easily and freely exchanged. A poem may never feed a family, but, to quote the napkin poet, “the destination is filling.”

Here’s my poem scrap written long ago for my friend Amanda, who first introduced me to Li-Young Lee and many other poets…

For Amanda

My friend stores away poems as if they were glittering treasures.

On special occasions, she brings them out to show you.

She tells you their story, one by one

How they were bought, discovered, given.

But instead of putting the bracelet back in its velvet pouch,

Hanging the necklace back on its golden hook,

Or nestling the ring back in its jewelry box,

She hands it to you, and lets you wear it home.

Pingback: Holiday Roundup | o wonderful, wonderful